The role of Human Rights in the effective implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

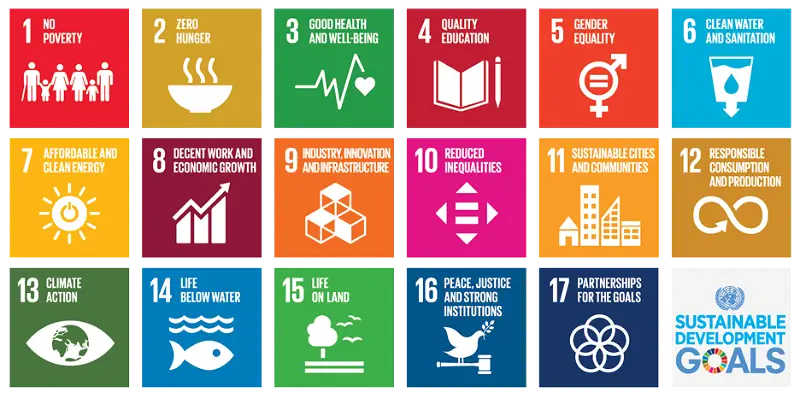

Over the past few decades the focus of development practice and theory was on human development, which culminated in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted in 2000 to enhance international and national development agendas. Fifteen years after, on 25 September 2015, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly (UNGA) adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development consisting of 17 new goals, coined the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs encompassed the three pillars of sustainability, namely, economic, social and environmental development.

According to the UNSG at the time, Ban-Ki Moon, the Agenda provides “a to-do list for people and planet, and a blueprint for success.” The 17 goals have been grouped into five categories, namely, (a) people; (b) planet; (c) prosperity; (d) peace; and (e) partnership. The first seven goals were formulated to address the gaps left by the MDGs and will require meeting basic human development needs. On the other hand, Goals 8 to 10 enhance “common drivers and crosscutting issues that are essential to advance sustainable development across all of the dimensions.” In addition, Goals 11 to 15 are focused on enhancing environmental sustainability, while Goals 1 6 and 1 7 aim to utilise a global partnership for development and the implementation of the goals.

The main objective of the SDGs, which came into force in January 2016, is to address new development priorities and challenges, as well as to close the gaps left by the MDGs. As with the original goals, the framework of the SDGs aims to eradicate poverty by the end of 2030 and inform national and international development priorities and action plans.

The framework also aims to promote a new world view and achieve sustainable development, that is, the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

According to the UNDP, in contrast to the MDG framework, the SDGs “have a more ambitious agenda, seeking to eliminate rather than reduce poverty.” Thus, the SDGs “go much further than the MDGs, addressing the root causes of poverty and the universal need for development that works for all people. The SDGs will now finish the job of the MDGs, and ensure that no one is left behind.”

However, despite the formulation of SDGs, the level of progress in their implementation is very low. Indeed, several factors continue to stall progress, as many development challenges remain unaddressed, including significant levels of inequality and poverty in several parts of the world. Stillbirth-rate and infant mortality, racial discrimination, discrimination against women, and systemic violations of the rights of the child continue to be reported in several countries. Access to quality education and to clean water remains a distant prospect for millions of children and women, especially in the developing countries. The world remains less inclusive.

As it was with the MDGs, human rights have played a limited role in the implementation and monitoring of the SDGs. While the SDGs give expression to all types of human rights, in practice the goals are not consistently, coherently and effectively aligned with human rights law and mechanisms.

However, many of the challenges confronting the implementation of the SDGs and impeding progress can be overcome if these goals are aligned with human rights law.

Integrating international human rights law and principles into the implementation and monitoring of the SDGs would provide the strongest and most accepted moral and legal bases for the progressive achievement of sustainable development.

The SDGs and human rights law have a shared objective of alleviating human suffering and increasing human development. However, significant differences exist between the two frameworks.

The SDGs focus on a limited number of issues which have implications for some socio-economic rights. In contrast, human rights law broadly embraces the notion of the universality and indivisibility of all human rights—economic, social and cultural rights as well as civil and political rights.

A human rights approach to the implementation and monitoring of the SDGs would not only incorporate the full spectrum of development capabilities, but also addresses the root causes of poverty and the lack of progress.

While the SDGs represent the best idea for focusing the world on fighting global poverty, progress in achievement of the goals will remain limited unless their implementation and monitoring are augmented by international human rights law.

Human rights law would enhance the ability of people—youth and the socially and economically vulnerable groups—to participate in decision making and voice their concerns and in fact challenge in courts the non-implementation of the SDGs by their governments.

The prospects of achieving gender equality and equal rights for all women and girls are brighter if the implementation and monitoring of SDGs are fully and effectively aligned with human rights law and mechanisms.

Consistently, coherently and effectively aligning the implementation and monitoring of SDGs with human rights law and mechanisms would contribute to addressing discrimination comprehensively, establishing global and national targets and timelines to fulfil civil and political rights and minimum essential levels of economic, social and cultural rights as legally enforceable human rights. It would also ensure that there are effective national and international accountability mechanisms to monitor the realisation of goals aimed at addressing poverty and exclusion and to provide redress for failures to respect and promote human rights.

The consistent and coherent implementation and monitoring of the SDGs in the light of states’ human rights obligations would also advance the human rights principles of universality, transparency, participation, equality, non-discrimination and accountability.

Unlike the SDGs, human rights law addresses the root causes of poverty and imposes certain obligations on states. For example, states parties to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women assumed legal obligations to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the two categories of human rights enshrined in these human rights treaties.

There are comparable regional human rights such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and the Arab Charter on Human Rights, which guarantee in varying degree these human rights.

These human rights treaties not only impose legal obligations on states parties but also grant victims of violations of human rights access to justice and effective remedies before national, regional and international human rights courts and institutions.

Poverty should be explicitly recognised as a violation of human rights for which states should be held accountable and victims should enjoy access to justice and effective remedies.

States should undertake appropriate legal reforms to empower individuals and groups to hold states to account for their implementation of SDGs in the context of their human rights obligations assumed under various human rights treaties to which they are parties.

States should also apply their international cooperation and assistance to the implementation and monitoring of the SDGs.

Consistent with the community of the international community to the SDGs, human rights treaty bodies, court and institutions should also seek to incorporate the SDGs in the exercise of the various mandates to interpret human rights treaties and to hold states to account for the breaches of these treaties.

Human rights lawyers should also familiarize themselves with the SDGs and proactively seek their implementation in the context of their public interest litigation to advance and promote human rights and seek justice and effective remedies for victims.

Youth organizations and women groups should work more closely with the human rights community and the development community to tap from the immense potential for a human rights approach to the SDGs.

Youth organizations and women groups can participate in the work of human rights treaty bodies and submit petitions to these bodies to seek redress and accountability for the non-implementation of the SDGs in specific countries.

These organizations and groups can also provide information to UN special rapporteurs, and treaty bodies (such as the Human Rights Committee, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and regional human rights mechanisms), and national human rights commissions on the non-implementation of the goals.

These proposed recommendations could serve to bring important publicity to the goals, improve states’ accountability for them and increase the possibility of access of victims to justice and effective remedies.

The recommendations could also help to keep governments’ feet to the fire, and strengthen the ability of youth organizations, women groups and civil society organizations generally to better contribute to the effective realization of the SDGs across the world.

In sum, the UN, UN member states, international organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), civil society, human rights and development practitioners must actively push for the consistent and coherent integration of the SDGs with international human rights law and principles if these goals are to be effectively implemented globally, and the debilitating factors impeding progress are to be overcome.

Ugochi Mercy-Okpe is executive director, Community Health and Advocacy Initiative (CHAIN). She delivered the paper at the AFS Youth Assembly meeting in New York.

Vanguardngr.com